The silence in the room is heavy, broken only by the creaking of wood and the collective held breath of 20 engineering students. A bucket fills with sand, ounce by ounce, suspended from a structure made of nothing more than balsa wood and glue. Then, a sharp snap. The bridge shatters, and the room erupts into a mix of groans and applause.

This is the quintessential experience of a student bridge design competition, but it comes with challenges. These obstacles serve as a bridge—pun intended—between theoretical textbook physics and the messy, unpredictable reality of construction.

However, your students pave the path to the podium with collapsed trusses and buckled beams. For students entering these competitions, understanding the specific challenges they will face is the first step toward engineering a winning structure.

The Rules of Strength-to-Weight Ratio

In professional civil engineering, the budget is usually the primary constraint. In student competitions, the budget is generally weighted. The most common metric for victory is efficiency: the load the bridge can carry divided by its own mass.

This creates a fascinating paradox. A heavy, solid block of wood might hold a lot of weight, but it will lose the competition because its efficiency score will be terrible. Students must learn to be minimalists. They have to identify exactly where material is needed and, more importantly, where it is not.

This challenge forces students to learn about stress distribution. They quickly discover that a uniform beam is rarely the most efficient design. Instead, they must experiment with tapering members or using hollow cross-sections to shave off grams without sacrificing structural integrity. The challenge lies in knowing when you have removed too much material, crossing the line from efficient to fragile.

Material Constraints and Fabrication Precision

Unlike the steel and concrete of the real world, student competitions often utilize specific, sometimes fragile, materials. Balsa wood, basswood, popsicle sticks, and pasta are common. These materials have natural imperfections. A knot in a piece of wood or a hairline fracture in a dried noodle can compromise an entire design.

The challenge here is twofold: selection and fabrication.

Material Selection

Students must learn to grade their materials. In a batch of balsa wood, the density and grain strength can vary wildly. Serious competitors will weigh every individual stick and categorize them. They use the densest, strongest pieces for members under high compression and lighter pieces for tension members or bracing. Ignoring the material properties is a rookie mistake that often leads to early failure.

The Human Error Factor

A design that works perfectly in a computer simulation can fail disastrously if the glued joints are weak. Fabrication precision is arguably the biggest hurdle for student teams. A joint that is slightly off-center introduces eccentric loading, which creates twisting forces (torsion) that you didn’t design the bridge to handle.

Furthermore, glue management is an art form. Too little glue, and the joint snaps. Too much glue, and the bridge becomes heavy and flexible, as many glues are not as rigid as the wood they bond to. Mastering physical construction is just as important as mathematical design.

Understanding Load Paths

When you look at a suspension bridge or a complex truss, it can be difficult to see exactly how the weight travels from the deck to the ground. In a competition, students must visualize this invisible path.

A major stumbling block is the failure to distinguish between tension and compression.

- Compression: Members are being squashed. If they are too long and thin, they will buckle (bow out) before they crush.

- Tension: Members are being pulled apart. Wood and steel are generally excellent in tension, but the joints that hold them together are often the weak link.

Students often design bridges that look sturdy but fail to account for how forces distribute dynamically. For example, under a heavy load, the top chord of a bridge is usually under compression. If your students don’t brace the top section laterally (sideways), it might snap sideways like a ruler being pressed at both ends.

This phenomenon, known as lateral torsional buckling, is a "silent killer" in competitions because it often isn't obvious in 2D drawings.

The Geometry of Stability

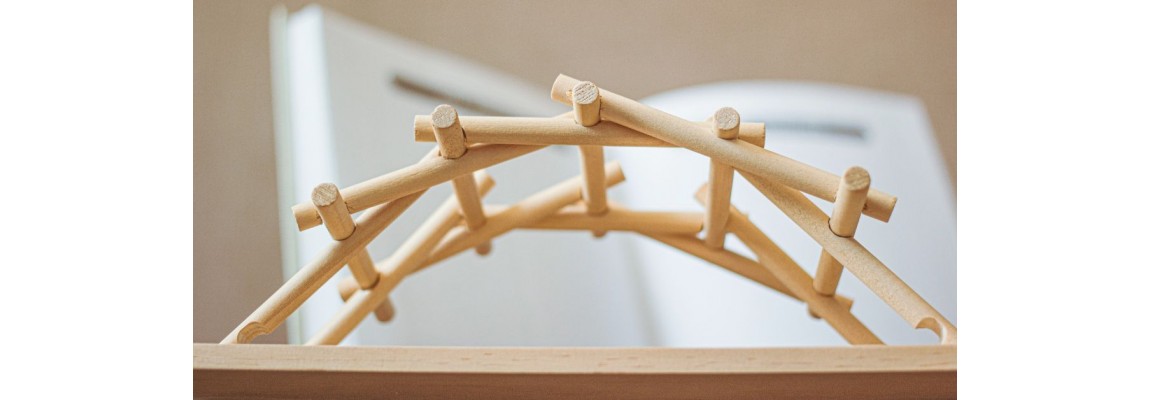

Why are bridges full of triangles? This is one of the first questions students answer through trial and error. A square is an unstable shape; push on the corner, and it collapses into a parallelogram. A triangle, however, is rigid. It cannot change shape without changing the length of one of its sides.

The challenge for students is arranging these triangles—the truss pattern—effectively. There are dozens of classic designs: the Warren, the Pratt, the Howe, and the K-Truss. Choosing the right geometry is a strategic decision.

The Warren truss uses equilateral triangles. It spreads the load well but requires strong joints. The Pratt truss is designed so that the longer diagonal members are in tension (where wood is strong) and shorter vertical members are in compression (where buckling is a risk).

A complex K-Truss might look impressive and theoretically handle loads better, but it involves significantly more joints and cutting, increasing the risk of fabrication error. A simpler Warren truss might be safer to build, but requires heavier individual members.

Environmental and Testing Variables

The day of the competition brings its own set of variables. In many competitions, the load isn't applied gently. Sand might be poured quickly, or a pneumatic press might shudder. These create dynamic loads—sudden forces that are much harder to withstand than a static weight resting quietly.

Students also face the challenge of the support conditions. In a simulation, a bridge support is a perfect, immovable point. In reality, the table might be uneven, or the testing blocks might slip. A bridge designed with zero tolerance for movement will shatter if the supports shift even a millimeter. Designing a structure that has a degree of forgiveness—structural ductility—is a lesson that often comes only after a heartbreaking failure.

Bridging the Gap to Success

So, how do students overcome these challenges? The answer lies in the engineering design loop: design, build, test, repeat. Teaching basic bridge design challenges helps students learn and prepare for future competitions.

Successful teams don't just build one bridge for the competition day. They build prototypes. They test individual joints to see how much glue is optimal. They construct single trusses and crush them to see where they break.

This iterative process allows them to identify weak points and fabrication errors before they count. For students new to building bridges, model bridge kits let them learn the basics with a guide.

AC Supply offers a variety of bridge-building kits to enhance your students’ experience and help them learn through hands-on projects. By mastering materials, geometry, and the art of precise construction, students do more than build a bridge; they create the foundational skills necessary for a career in engineering.